Fourth Quarter 2022: Rolling Boil to a Simmer

By: Eric Schopf

The year 2022 was defined by broad inflationary pressures and the Federal Reserve’s efforts to reestablish price stability. Two additional interest rate hikes during the fourth quarter demonstrated the Fed’s resolve. The federal funds rate stood at just 0.25% as recently as March, but following seven rate increases, the rate closed the year at 4.5%. The goal of all central bankers during an inflationary cycle is to engineer a soft landing by reducing inflationary pressures through higher interest rates. The trick is to raise interest rates high enough to contract demand without tipping the economy into recession.

Economic data is beginning to indicate that the Federal Reserve, with Jerome Powell at the helm, may be close to accomplishing this rare feat. The optimism was on full display during the quarter. The Standard and Poor’s 500 stock index provided a total return of 7.1%, with no daily close below the September 30 index level. The strong quarter limited the loss in the S&P 500 to 18.1% for the year. The 10-year United States Treasury bond advanced only one basis point in the quarter and closed at 3.81%. Bonds experienced greater volatility than stocks, with the 10-year touching 4.23% in October before beginning its descent.

Market optimism is pinned on the hopes that the Fed is close to the end of its rate hiking cycle. Although inflation is no longer running at a rolling boil, the current simmer is not in line with the Fed’s 2% goal. Additional rate hikes may be necessary to restore the slow simmer that prevailed prior to the pandemic. The order and magnitude of additional rate increases depend on the economic data, and obstacles to achieving the 2% target include a strong labor market, easing financial conditions, a generally strong economy and shifting consumer demands.

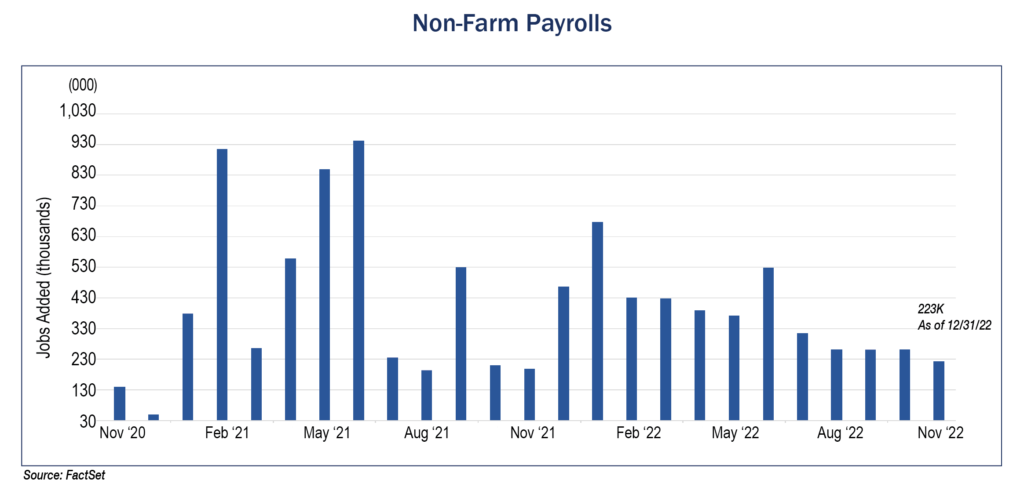

Job growth has been extraordinary. The three-month average job growth during the quarter has been nearly 250,000, and the unemployment rate is just 3.5%. Consumer spending represents roughly two-thirds of the United States economy, and the consumption demand machine, fueled by full employment, should continue to chug along.

Other factors to consider are the prevailing market conditions. The financial markets are the transmission mechanism for monetary policy, and premature shifts in interest rates may buoy consumer demand and undercut the Fed’s intentions. The mantra on Wall Street has been “higher for longer” concerning interest rates. With interest rates in decline since October, the Fed may have to push back even harder to meet its goal. It has become commonplace to see Fed Governors jawbone the markets lower through media appearances. Television and radio spots are a not-so-gentle reminder that the fight continues and may not conclude until the ideal inflation rate is reached.

Following a rough first half in 2022, economic growth has resumed. Higher interest rates have taken a large bite out of the real estate market with new home and existing home sales plunging. New vehicle sales have also fallen. Nonetheless, the overall economy grew by 3.2% in the third quarter, and growth would have been stronger if not for inventory accumulation. Warehouses are packed with excess goods and have no need for replenishment.

The shift in consumer buying is also impacting the inflation fight. During the pandemic, consumers who were stuck at home went on a product-buying binge. Three years later, buying products has been replaced with buying services. Consumers are spending on vacations, dining and entertainment, and this increased demand for services is now pushing labor prices higher. Because labor supply is thin with unemployment at low levels, wage pressures are likely to persist.

Although obstacles are still present, we are beginning to see signs that the rate-tightening cycle is almost over. We don’t want to extrapolate too much from recent data points, but the evidence of deceleration in prices caused by higher interest rates is becoming clear.

Headline inflation data can be deceiving. Data, gathered and disseminated by the Bureau of Labor and Statistics, is often reported in year-over-year comparisons. The December data release, which covers the period through November, indicated an all-items increase of 7.1% year-over-year. Core inflation, which excludes food and energy, grew 6%. However, the month-over-month change from October to November showed real signs of improvement. The all-items month-over-month growth was just 0.1%, and the core rate was under 0.4% for the first time since August 2021. Producer prices are showing a similar trend. Lower demand due to higher prices and the shifting of discretionary spending towards services have helped to put the brakes on price increases. Most pandemic supply disruptions have been resolved, which has resulted in additional price relief.

Although job growth had been robust, the recent moderation of job growth has been favorable for the Fed. The three-month job growth average has been the weakest since the November 2020 through February 2021 time period. Recent high-profile layoffs announced by Amazon, Goldman Sachs, Salesforce and Meta (Facebook) are signs that the unemployment rate will begin to move higher. Hoarding workers may be coming to an end as companies seek to reduce expenses in order to meet earnings growth targets. The reduction in job growth is evidence that restrictive monetary policy is having the desired effect.

Light at the end of the rate-tightening cycle doesn’t mean we are out of the woods. Additional rate hikes and further layoffs could easily create negative momentum. It took the Federal Reserve almost thirty years to control inflation following the out-of-control 1960s and 1970s. The current bout of inflation may take longer than anticipated to corral. The impact of interest rates remaining higher for longer is uncertain, and this uncertainty breeds risk.

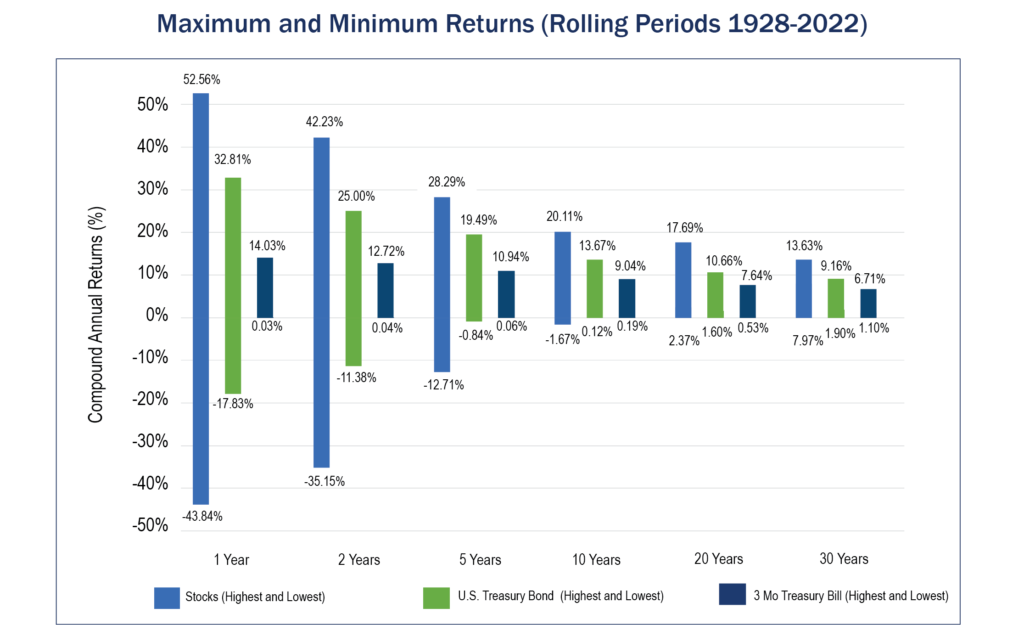

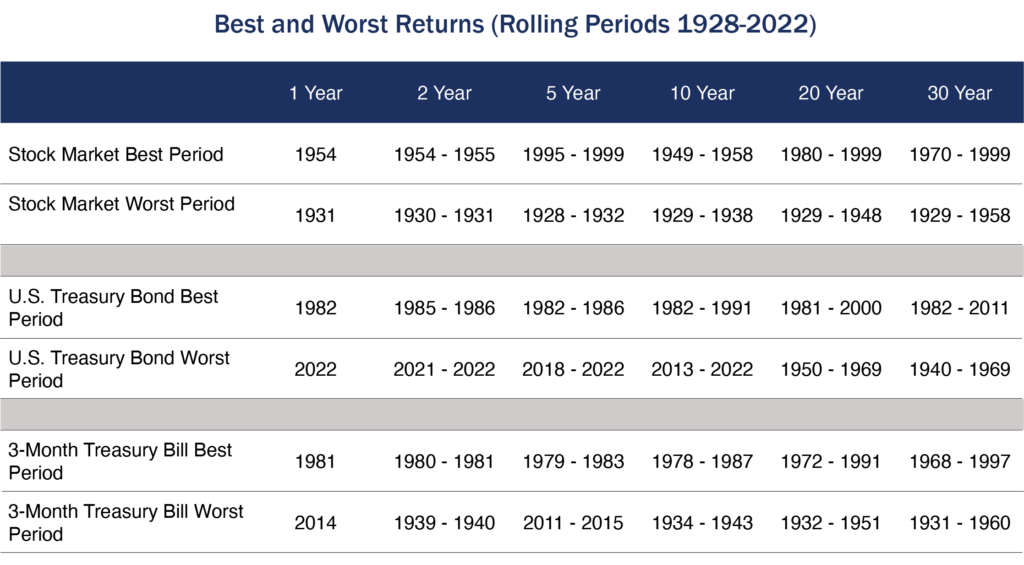

It has been empirically demonstrated that over the long run, common stocks offer superior returns when compared to bonds and Treasury bills, albeit with a higher level of risk. However, over shorter periods of time (periods of less than five years), returns and risk can gyrate wildly for all asset classes. The Returns Chart (on page 3) shows the maximum and minimum returns for the different asset classes for different rolling periods dating from 1928 through 2022. The pandemic period is a reminder of volatility in the short run. It is too early to say with certainty how or when the current economic cycle will end, but we can say with certainty that this won’t be the last cycle.

When it comes to investing, time is your friend. It is said that the market takes from the impatient and gives to the patient. Put time on your side by making sure that your asset allocation is consistent with your investment time horizon and risk profile.