Third Quarter 2023: Are we there yet?

By: Eric Schopf

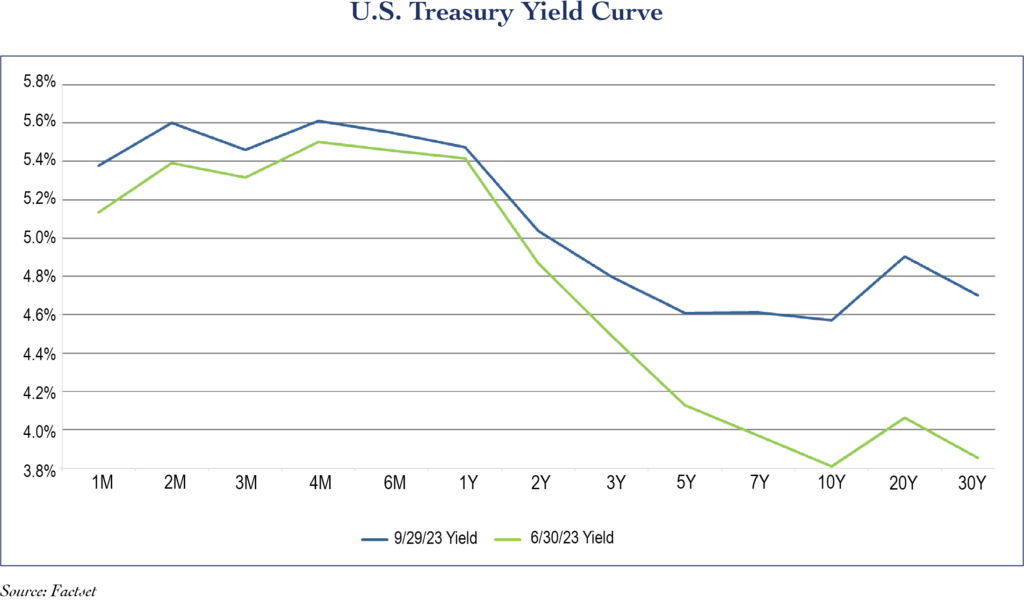

The third quarter was punctuated by a substantial move higher in interest rates. After pausing in June, the Federal Reserve increased the federal funds target rate by an additional quarter percent in July to 5.5%. The inversion of the yield curve over the past year reflected the market’s expectations for a bull-steepening move in rates, where short-term interest rates drop to restore financial order. Although the Fed hit the pause button again in September, the market has capitulated and now embraces the idea of a sustained period of restrictive policy. Higher-for-longer resulted in significant rate increases across the yield curve. Maturities of ten years and greater increased the most, reflecting the shift in expectations of the current cycle. Instead of the bull steepening, we are getting a bear steepening with the higher long-term rates. The higher rates created a headwind for stocks, and the Standard & Poor’s 500 index fell 3.27% during the quarter.

The American economy continues to show tremendous resilience, and employment has been the star of the show. The first read of September payrolls showed an increase of 263,000 jobs, far more than the consensus estimate of just 170,000. Equally impressive were the revisions to the August and July reports. August payrolls were revised from 187,000 to 227,000 and July from 157,000 to 236,000. The eleven interest rate increases over the past seventeen months have been one of the most aggressive campaigns ever undertaken by the Fed in terms of both magnitude and duration. Despite the restrictive policies, the unemployment rate is just 3.8%. The strong job market sustains consumer spending, and consumer spending drives 70% of the U.S. economy. The next Fed meeting is in November, and all eyes are trained on their next move. The big jump in rates during the quarter makes their job a little easier. Although rates may be increased by another quarter point, the bigger issue becomes dealing with the high rates for a longer period of time.

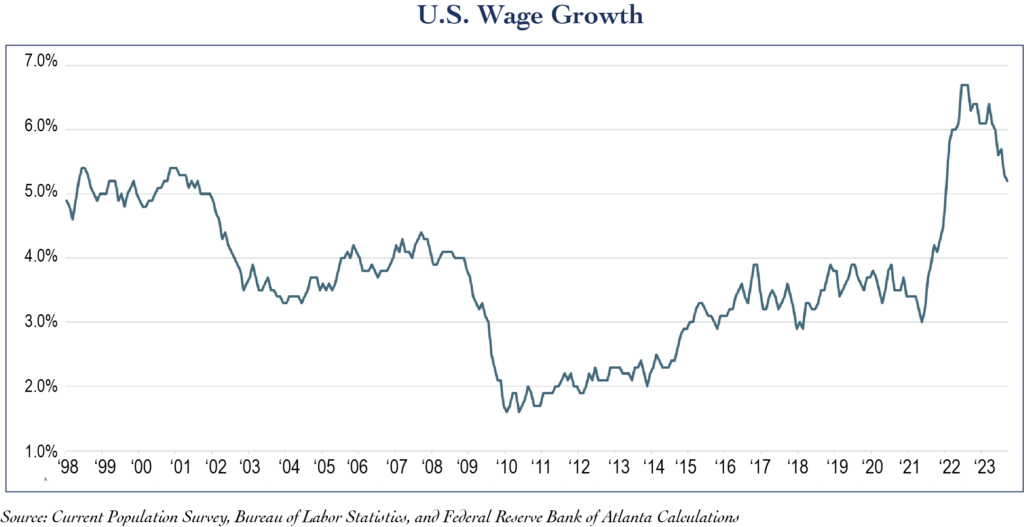

With employment still robust, the Fed is most interested in inflation, but they continue to see improvement. The core consumer price index, which excludes food and energy, rose at an annualized rate of 2.4% in August, and this is very close to the Fed’s inflation target of 2%. Energy, however, is an important inflation variable, even if its prices are beyond the Fed’s control. Crude oil production cuts by Saudi Arabia in June resulted in a sizeable global price spike. West Texas intermediate oil jumped from $70 per barrel on June 30 to $91 per barrel on September 30. Average hourly earnings growth has also moderated. Growth peaked at 5.11% in June of 2022 and has been trending lower ever since, and this moderation has quelled fears of a wage-price spiral. Nonetheless, high profile negotiations by the Teamsters and the United Auto Workers are evidence that labor still has leverage and wage pressures are still a potential flash point. Producer prices have also decreased with growth rates having returned to pre-pandemic levels. Most importantly, the Personal Consumption Expenditure Price Index also continues to trend lower. This inflation gauge, which considers everything from car prices to clothing and food to housing and healthcare, remains stubbornly above the 2% inflation target. This is another reason why interest rates may remain higher for a longer period of time

Quantitative tightening and deficit spending are contributing to supply/demand imbalances in the credit market, putting further pressure on interest rates. After accumulating nearly $9 trillion in fixed income assets during the pandemic, the Fed has slowly let the balance run off through maturities. The balance now stands at $8.1 trillion. At the same time, federal spending has resulted in an explosion of U.S. Treasury bond issuance. Treasury debt outstanding at the close of the second quarter was $25.4 trillion, and by the end of the third quarter, the balance had grown to $26.3 trillion. The 3.5% increase in only three months is enormous! Our nation’s outstanding debt was a mere $17.1 trillion in December 2019, just as the pandemic was starting. Absent the Fed’s buying power, finding buyers for the additional debt will require higher interest rates.

Not only is the absolute level of debt ballooning, but the cost of the debt is now at a fifteen-year high. The average weighted maturity of U.S. debt is six years, and the average monthly interest rate is about 3%. As bonds mature, new issues are sold with higher coupons. The interest service on the debt is becoming a greater issue because interest payments will reach 4% of our gross domestic product in 2024. This is the highest level since the 1980s. The interest expense now consumes 11% of all federal government spending, and this growing debt burden is putting greater pressure on our political leaders in Washington. Congress was able to avert a government shutdown in September, but it cost the House Speaker his job. It was a high price to pay for a continuing resolution that only temporarily keeps the government open through November 17 of this year.

Higher interest rates are impacting corporations as well. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, 516 corporations have declared bankruptcy through the third quarter of 2023. The Yellow Corporation, a large trucking company, and Bed Bath & Beyond, a home goods retailer, were two of the larger cases. Zombie companies, who earn just enough money to continue operations and to service their debts, had been clinging to a lifeline of lower interest rates. Now that the rates are rising, they are being set adrift. The tide is going out, and we know who has been swimming naked.

The resilient U.S. economy can be linked to several factors. Excess savings accumulated during the pandemic have fueled consumption. Massive deficit spending has also showered the economy with money. The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, which provides $280 billion in new funding to boost domestic research and manufacturing of semiconductors, is just one example. The aging workforce and acceleration in retirements have tightened the labor market, keeping unemployment low and wages up. Or perhaps it’s the Taylor Swift tour? Regardless of the causes, traditional monetary policy strategies have been slow to achieve the desired effect of lowering inflation. Until the rate of inflation is reduced, we can expect the current policies to remain along with the concurrent volatility.