Value Investing or Investing for Value

Value is in the eye of the beholder. I have been in the investment business for 18 years and have met all kinds of different investors—growth, value, momentum and technical. The one common thread among them is that they believe they are purchasing stocks at a good value. Quite simply put, they are buying a stock trading below their estimate of what it is worth. In this sense, all investors are investing for value. But value investing trumps investing for value over long periods of time.

Value is in the eye of the beholder. I have been in the investment business for 18 years and have met all kinds of different investors—growth, value, momentum and technical. The one common thread among them is that they believe they are purchasing stocks at a good value. Quite simply put, they are buying a stock trading below their estimate of what it is worth. In this sense, all investors are investing for value. But value investing trumps investing for value over long periods of time.

Investing for value and value investing are very different. Value investing is an often-misunderstood investment style. Benjamin Graham and David Dodd are the founding fathers of value investing. Their book Security Analysis is still considered the bible for true value investors and a must-read for all investors. Although value investing has evolved over time, it is based on fundamental analysis used to derive the intrinsic value of a company. This calculated value is compared to the current share price for relative attractiveness. Ratios like price-to-book value, price-to-sales, priceto- earnings and price-to-cash flow are used to assist in valuation. Typically, value investors will purchase stocks where the intrinsic value is sufficiently below the current stock price and whose valuation multiples are at the lower end of their historic ranges. Finally, value investors are often, but not always, “bottoms up” investors, which means they pay very little attention to the economic cycle—they are evaluating the company on its own merits.

While the value philosophy has a straightforward definition, it is far more difficult to define a value stock. There is not an agreed-upon definition, and each value index defines value stocks a little differently. Standard and Poor’s, probably the most well-known and respected creator of indexes, defines value for their value indexes using four variables: book value-to-price, cash flow-to-price, sales-to-price and dividend yield. Interestingly, the most commonly used value ratio, the price-to-earnings ratio, is not used. To complicate the issue, the current S&P 500/Citigroup Value Index holds 374 different companies, of which 160 (42.7%) are also in the S&P500/Citigroup Growth Index. A staggering 55.9% of the companies in the growth index are also in the value index.

While the value philosophy has a straightforward definition, it is far more difficult to define a value stock. There is not an agreed-upon definition, and each value index defines value stocks a little differently. Standard and Poor’s, probably the most well-known and respected creator of indexes, defines value for their value indexes using four variables: book value-to-price, cash flow-to-price, sales-to-price and dividend yield. Interestingly, the most commonly used value ratio, the price-to-earnings ratio, is not used. To complicate the issue, the current S&P 500/Citigroup Value Index holds 374 different companies, of which 160 (42.7%) are also in the S&P500/Citigroup Growth Index. A staggering 55.9% of the companies in the growth index are also in the value index.

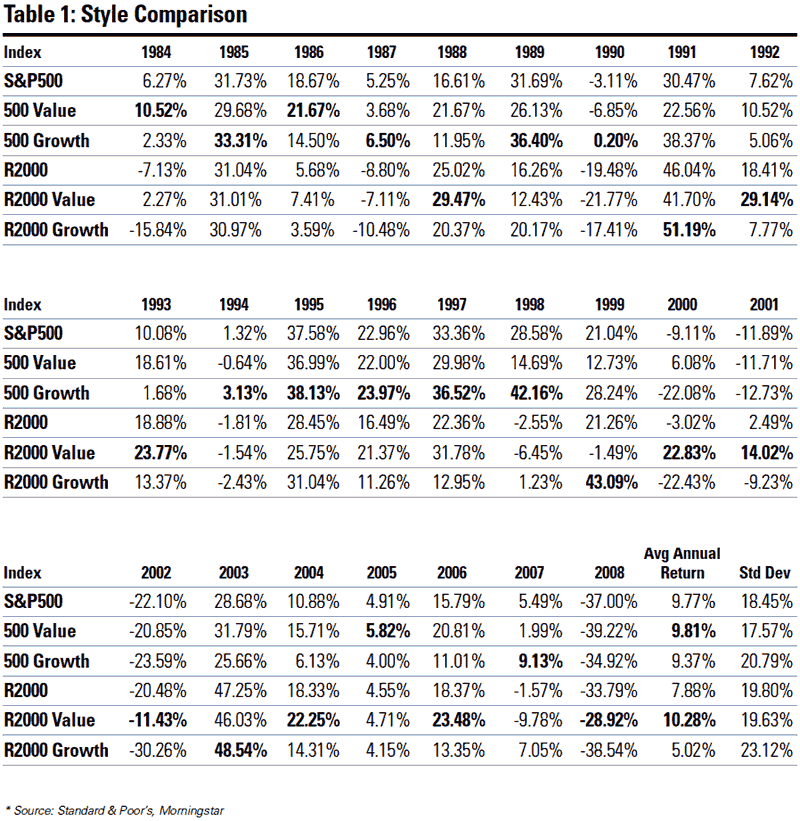

Studies show that value investing is the superior style choice over long periods of time . As we can see from the chart below, over the last 25 years, the value style has the highest rates of return while taking lower risk. This dynamic is what investors should seek to maximize. Within small capitalization stocks, as measured by the Russel 2000, the difference is even more pronounced. To be sure, in any given year, different investment styles will work better than others. But, over the long term, value has proven to be the best investment style for investors.

Given the information in Table 1 (above), it is not wise to commit all of your money to one style as history shows that any one style can underperform others for long periods of time. Growth, as measured by the S&P 500/Citigroup Growth Index, has outperformed value in 13 of the 25 years. Value, though, has provided a higher return with less risk. Diversification among styles is just as important as it is among securities and asset classes. Blending the two styles in your portfolio is the strategy that should provide the most consistent returns for your portfolio.

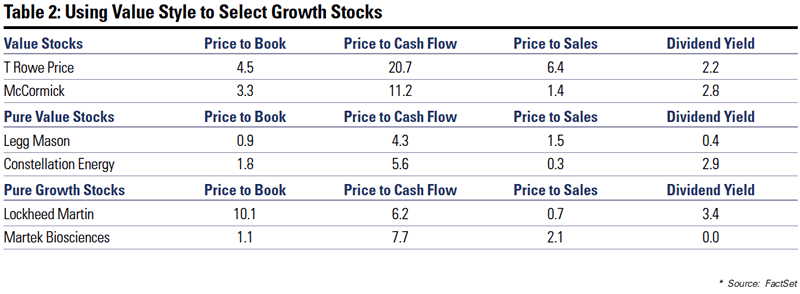

[blockquote4]The value philosophy can be used to get exposure to other investment styles.[/blockquote4]The value philosophy can be used to get exposure to other investment styles. This is done by screening for value attributes on all stocks, not just stocks of a specific style. A multitude of stocks can be identified that would otherwise be overlooked, as they may not fit the definition of value. Table 2 (below) presents a comparison of six different companies—two value, two pure value and two pure growth. “Pure value” and “pure growth” are defined as stocks that are only in each respective index. Clearly, the two pure value stocks are the cheapest on a valuation basis. Interestingly, though, the pure growth stocks are relatively cheaper than the value stocks. This is due to the industries in which these pure growth companies operate—defense and biotechnology. With budget deficits skyrocketing and impending regulation in healthcare, these two stocks are out of favor with investors, causing low valuations. Value investors can take advantage of cheap growth stocks and not give up their discipline.

The purpose of the data is not to recommend purchase but to illustrate that using the value philosophy can unearth some hidden gems in every area of the equity market. Having a disciplined, consistent investment approach employing the value philosophy can lead to superior returns over time. Diversification among stocks of different styles is just as important as diversification among asset classes. While diversifying among stocks, employing the value philosophy rather than “investing for value” should lead to superior results. Isn’t that the real value in investing?

—as published in CFA Society Baltimore’s annual Baltimore Business Review