First Quarter 2022: Actions Speak Louder Than Words

By: Eric Schopf

The first quarter of 2022 was a struggle for the financial markets. A more hawkish Federal Reserve combined with the Russian invasion of Ukraine resulted in the steepest losses for stocks since the first quarter of 2020. The bond market suffered its worst loss since the financial crisis in 2008. Just as the Omicron wave of Covid-19 peaked and supply chain issues eased, we were presented with a new set of problems.

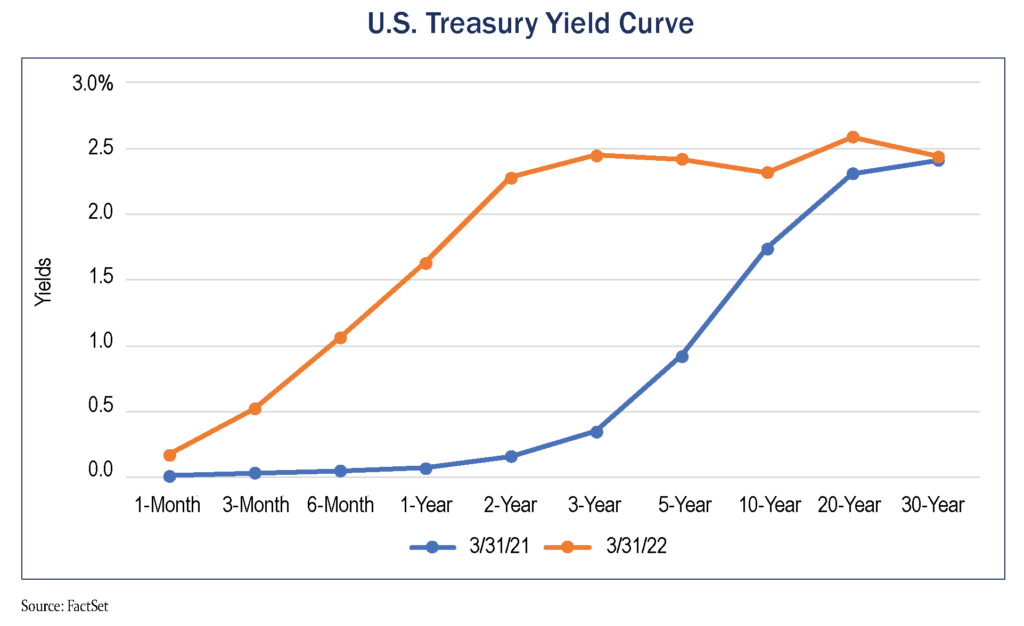

The stock market peak for the quarter was set on January 4 and the trough came on March 8, representing a price decline of 12.5%. A strong recovery during the last few weeks of March limited the damage to just 4.6% for the first quarter. The bond market fared much worse. The 10-year United States Treasury bond yield moved from 1.52% to 2.32%. The Bloomberg U.S. Intermediate Government/Credit index, which tracks the performance of intermediate-term U.S. government and corporate bonds with an average maturity of about 4.5 years, dropped 5.01% in price.

The Federal Reserve delivered the greatest impact on first quarter results. Rhetoric turned to action when the Fed raised the federal funds rate by 0.25% during its March meeting. Inflationary pressure, generated by the massive printing of money during the pandemic, could no longer be explained away as “transitory”. Members of the Fed have been very visible and vocal in announcing the need for further interest rate increases to bring inflation under control. Estimates range from six to nine additional hikes in increments as high as 0.50%. Quantitative tightening will accompany the rising of interest rates. The Fed accumulated over $5 trillion in additional assets through quantitative easing, and they now hold over $9 trillion of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities. They plan to reverse the process by letting bonds mature without reinvestment. Fed meeting minutes indicated that the balance sheet reduction could start as early as May with monthly runoffs of $60 billion of Treasuries and $35 billion of mortgage-backed securities. Passive removal of $95 billion per month may not be enough to move the needle, however. Outright security sales may be needed to further raise interest rates, slow the economy and bring inflation down to more reasonable levels.

Beyond the obvious human tragedy, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has complicated the economic landscape. The invasion, which seems very 20th century with tanks and mass destruction, has added to global inflationary pressure due to export disruptions from Russia and Ukraine. Together, the two countries provide around 14% of the world’s wheat supply and 25% of global wheat exports. Most European countries are oil and gas importers, and economic disruption due to higher energy prices will greatly impact them. The Fed acknowledged that the invasion led it to initially delay monetary action due to these uncertainties. Broad and deep sanctions will greatly impact the Russian economy, but not before the boundaries of eastern Europe are redrawn. The quick victory that Russia hoped for has turned into a protracted and bitter dispute. A return to pre-invasion trade policy will not occur anytime soon.

Inflation has emerged as the post-pandemic boogie man. The Fed pivoted from favoring full employment to bringing stability back to the dollar. An upward spiral of higher prices leading to higher wages leading to higher prices is their greatest fear. Higher interest rates, a somewhat blunt tool, is one of the few options available to help reduce demand and slow the economy. Payments, most notably with mortgages and automobile loans, will be more costly to consumers. At the same time, the best cure for high prices can be high prices. Demand destruction will set in as many consumers will eventually do without. However, raising interest rates excessively, coupled with falling demand, can lead to a recession.

The talk of recession became a steady drumbeat over the last few months. This fear emerged during the backdrop of an otherwise robust economy. Fourth quarter gross domestic product growth was 6.9% and full-year growth was 5.5%. The unemployment rate stands at just 3.6%, and initial jobless claims are at the lowest levels since September 1969. The manufacturing sector of the economy is humming and services are regaining their footing. At the same time, people are coming back into the workforce in order to pay the increasingly higher prices.

While the economy is quite strong, we are beginning to see signs of stress, and inflation skews most reported economic data. As an example, retail sales, an indicator of consumer strength, is reported in nominal dollars. Adjusted for inflation, growth has been weak, and personal disposable income tells a similar story. Headline numbers look strong, but when adjusted for inflation and taxes, real disposable income is falling. Excess savings during the pandemic and inflated asset prices have helped consumers offset higher prices, but savings rates are dropping as more income is required to cover basic living expenses.

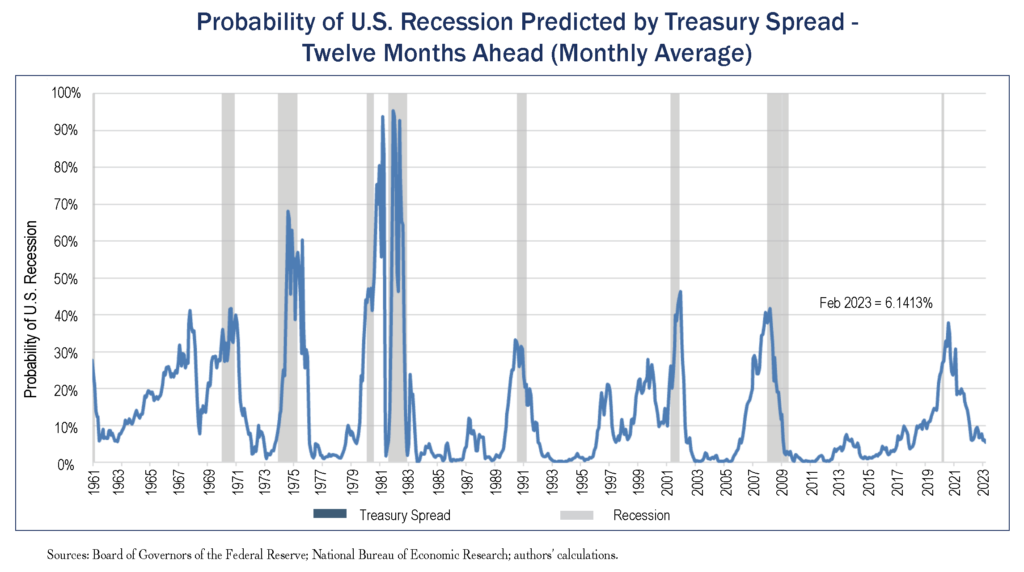

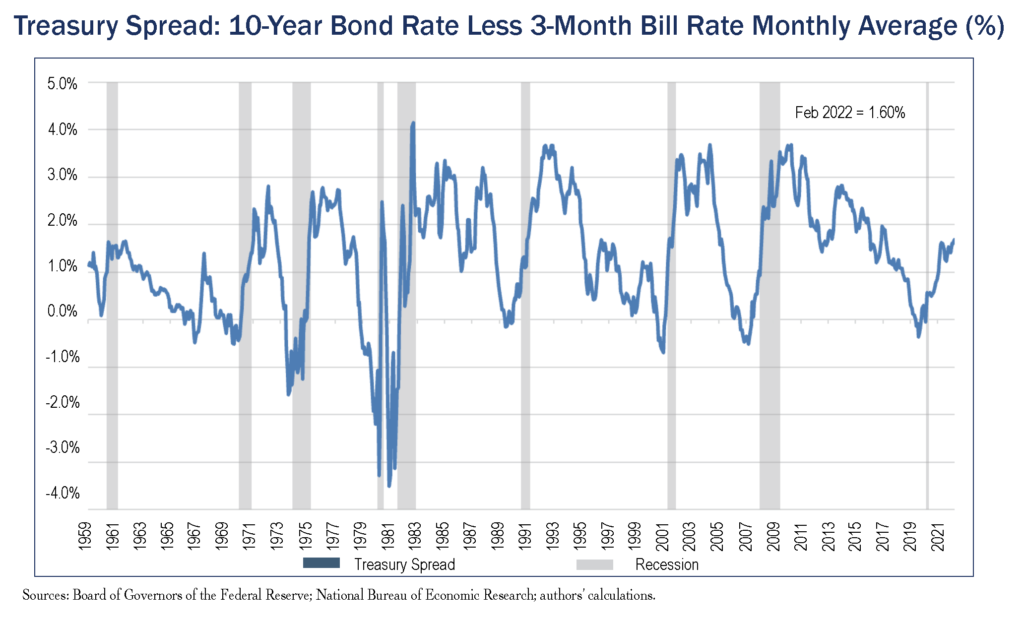

These mixed signals create uncertainty. The best recession indicator we have is the yield curve. The graphic below compares interest rates across the maturity spectrum. A normal yield curve reflects short-term interest rates that are lower than intermediate rates and intermediate rates that are lower than long-term rates. Yield curve inversion, when short-term rates or intermediate-term rates are higher than long-term rates, is a reliable indicator of recession. The U.S. curve has inverted before each recession in the past fifty years. It offered a false signal just once in that time. When short-term yields climb above longer-dated ones, short-term borrowing costs are more expensive than longer-term loan costs. Under these circumstances, companies often find it too expensive to fund their operations, which results in the reduction or elimination of investments. Higher borrowing costs also lead to a cutback in consumer spending.

The current yield curve is a mixed bag. The two-ten spread, the difference between two-year and ten-year treasuries, inverted during the quarter. However, the three-month, ten-year spread is still quite wide. We have used the three-month ten-year treasury spread as our primary indicator. Although the three-month, ten-year spread isn’t reflecting recession today, the trajectory of short-term rates is clearly rising to hopefully combat inflation. The yield curve will most likely invert later this year or early in 2023 depending on the size of interest rate hikes. As reliable as the yield curve may be in predicting recession, its timing and magnitude are imperfect. Given this uncertain horizon, we at Tufton Capital will exercise caution before deploying money into new investments.

The Covid virus continues to frustrate. Although case volumes have dropped precipitously in the United States, China is experiencing fresh outbreaks. Shanghai, their leading industrial and manufacturing center, entered lockdown in late March. We have seen this movie before, and it is not good. Supply disruptions just feed into the current inflationary narrative.

The volatility experienced in the first quarter should persist throughout the year. The days of easy monetary policy are over for this economic cycle. The degree of tightening needed to arrest the worst bout of inflation in over forty years may be greater than the market anticipates. Although we have been cautious in adding stocks to our portfolios, we are experiencing an opportunity to earn interest rates that have spiked to levels seen just two other times over the last decade.